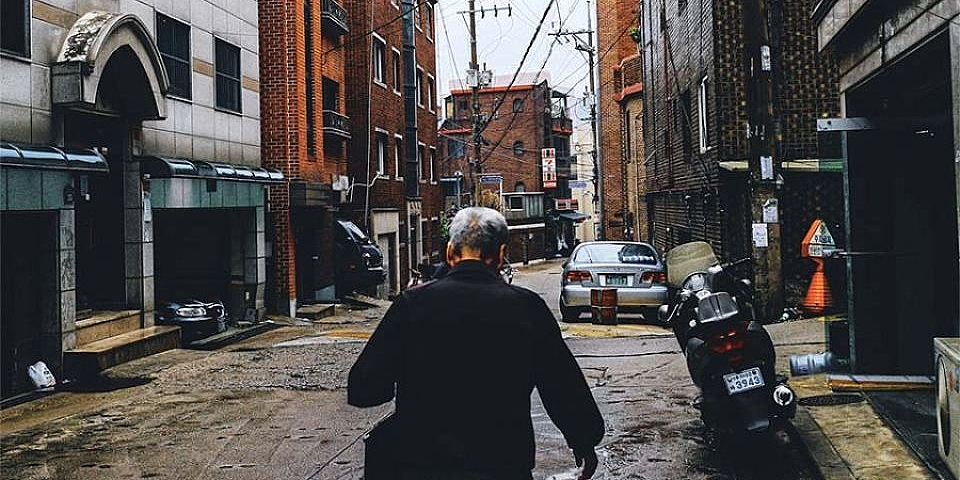

SEOUL: The number of South Korean workers aged 65 and older has overtaken that of those aged 15 to 29 for the first time, pointing to a host of troubling issues for the country where the fast-aging population confronts a lack of post-retirement support.

According to Statistics Korea, the average number of employed elderly workers reached 3.94 million in the second quarter of this year, surpassing the 3.8 million employed young adults during the same period.

Those aged 65 and older secured 231,000 jobs out of the 261,000 jobs added last month.

The noticeable surge in older workers has pushed the economic participation rate of over-65s to 40 per cent, the highest among OECD member countries.

The dramatic change in job data seems inevitable.

When the Korean government began to compile employment figures in the first quarter of 1989, there were 4.87 million young adult workers, outnumbering a small number of senior workers.

But senior employment surged as a result of extremely low birth rates and a rapidly aging population in the following years.

In 1992, the country’s elderly population was estimated at 2.36 million, which is about 18 per cent of the younger people aged 15 to 29 at the time.

In February 2022, the elderly population stood at 8.94 million, overtaking the younger demographic.

In July this year, the senior population exceeded 10 million, accounting for 19.6 per cent of the total population.

With nearly 1 in 5 people aged over 65, Korea is headed for a super-aged society, where the elderly make up more than 20 per cent of the population.

The growth of the older population is one reason behind the ballooning pool of senior workers in recent years.

But there is one embarrassing reason: the need to make a living, even after retirement.

Many retirement age people are seeking jobs or trying to stay employed since they do not have reliable income sources to maintain financial stability.

The primary factor is that Korea’s pension system offers a low payout of about 600,000 won (RM1,900) on average per month — an amount that is too low to pay for rising taxes, utility bills and other living costs.

Worse, the age of pension eligibility is unfavourable for many seniors.

The national pension scheme starts paying benefits at 63 for those born between 1961 and 1964. The eligibility age goes up to 64 for those born between 1965 and 1968, and 65 for those born after 1969.

This means that many elderly people have to struggle to make a living for up to five years — a period when they neither have a job or the eligibility to get the national pension payment.

Despite the challenging income gap that retirees must face, the Korean government and companies are yet to discuss extending the retirement age beyond 60.

With the absence of new policy formulation, retirees have no other choice but to seek jobs to bridge the income gap, which is now reflected in the growing senior employment.

The underlying problem is that senior workers are rarely offered stable, high-income jobs.

The government currently provides part-time jobs to seniors, but most of the state-sponsored positions offer a low monthly income between 290,000 won and 760,000 won, and the type of work is mostly low-skilled.

These structural issues aggravate the problems related to the elderly population.

Government data, for instance, shows that nearly 40 per cent of South Koreans over 65 are living below the OECD poverty line, set at half the national median income.

Beginning this year, the 9.54 million second baby boomer generation, born between 1964 and 1974, are set to retire over the next 11 years.

Helping these well-educated second baby boomer retirees and other aging population into the workface can reinvigorate the country’s economic growth.

The government and companies must start exploring ways to leverage senior workers’ expertise and experience instead of letting them struggle with low-skilled, temporary work.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT