If he wins the United States presidential election in November, Donald Trump will almost definitely scrap the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement as he did in 2016.

But Joe Biden restored the US commitment to the agreement after he replaced Trump in 2020.

Back in 2001, another Republican president, George Bush, withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol, and several other countries, such as Japan and Russia, followed suit.

From a climate change perspective, there are five “champions” of the world’s CO2 emissions: China, the US, India, Russia and Japan.

Based on 2022 data, China emitted 11.4 million tonnes of CO2 gas from fossil fuels, mainly coal. About 58 per cent of the total energy generated by China comes from coal.

The US came second with total emissions of 5 million tonnes in 2022, mostly from transportation, electricity generation and industry.

The US economy relies heavily on the transportation sector, which uses oil to fuel trucks, ships, trains and aircraft.

Reliance on cars as the primary means of transportation contributes to the country’s carbon footprint through gasoline and diesel.

India ranked third, with 2.8 million tonnes of carbon emissions from coal as a primary energy source, supplying about 44 per cent of the country’s energy needs.

Russia is the world’s fourth largest carbon emitter, with 1.7 million tonnes, which is not surprising as coal is widely used in the chemical industry and for power generation there.

Japan is fifth, emitting about 1 million tonnes of carbon in 2021.

The central energy fuel mix in Japan changed after the nuclear accident at Fukushima in 2011. Since then, oil has become Japan’s largest energy source, with a share of 38 per cent in 2021.

Coal is the other largest energy source in Japan, accounting for about 25 per cent of the energy mix.

In the arena of global climate change negotiations, the US has always come under the spotlight and served as a reference among signatories to the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

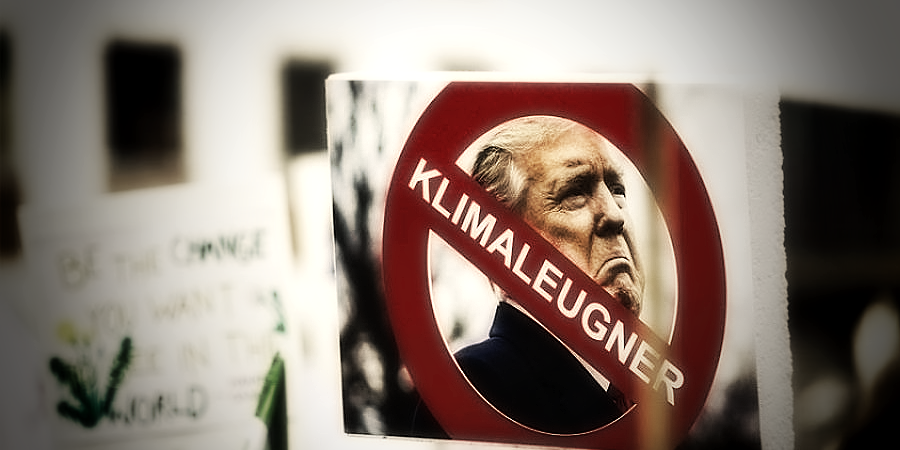

Trump is infamously known for altering the map of global climate change agreements by opposing efforts to limit CO2 emissions at home and internationally.

This stance appears rooted in his administration’s electoral populism and economic nationalism, a particular interpretation of individual liberty and the belief that humanity has the right to exploit nature.

Article 4.11 of the Paris Agreement stipulates that each country “may adjust” its emission reduction contribution by its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) target at any time.

However, this must be done to increase its level of ambition, and not the other way around.

The Paris Agreement was designed in such a way that allowed the US government to adopt it through a presidential executive order.

While this legal tool makes it easier for Trump to withdraw from the contract, it will also make it easier for other presidents to re-join.

The critical question is whether the US will seek to identify “appropriate terms for reengagement” and what this might mean in practice.

Indonesia’s commitment to climate change policies is reflected in its NDC, which is basically translating the Paris Agreement into climate action.

To this end, Indonesia has set various climate targets, including through its 2022 Enhanced NDC to reduce up to 43.2 per cent of its emissions by 2030, with an optimistic scenario of reaching net-zero emissions by 2060 or earlier.

Additionally, indicative pathways toward the long-term climate actions are stipulated in the Long-Term Strategy on Low Carbon and Climate Resilient Development (LTS-LCCR) 2050.

Indonesia has implemented a moratorium on permits for clearing pristine forests, established a peatland and mangrove restoration agency and strengthened its forest fire fighting capabilities.

In the energy sector, Indonesia’s 2021–2030 electricity supply plan targets half of its new power generation to operate on renewable energy.

At the same time, the deployment of renewable energy and energy efficient technologies has been modest, with the country maintaining a heavy reliance on coal for power generation.

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) is investing US$71.8 million (RM312 million) over five years, subject to the availability of funds, to support Indonesia in tackling the global climate crisis.

USAID contribution is particularly focused on the Climate Change Adaptation Plan. This plan was later integrated into Indonesia’s 2020–2024 national development plan, which allocated over $2.4 billion in the funds for climate change adaptation.

Trump’s antipathy to climate action, however, will have a significant impact, not just in the US but in many parts of the world, including Indonesia.

A Trump return to the White House could disrupt hopes of achieving net-zero emissions.

In the US, the worrying picture could include rollback from Biden’s ground-breaking climate change legislation, withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and a push for more oil and gas drilling.

From an international perspective, US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement would weaken the foundations of global climate governance and set a bad precedent for international climate cooperation, undermining global trust in climate cooperation.

The global effort to achieve the ambitious emissions reduction targets under the Paris Agreement to peg the temperature rise at 1.5 degrees Celsius still needs to be completed.

However, we are facing a situation where setbacks to these efforts are not just possibilities, but imminent risks.

The only hope that the global community is waiting for is strong leadership that could come from anywhere, including Indonesia.

In addition, China, as the world’s top emitter, must take the initiative to do something and set a concrete example of climate action that other countries can emulate and develop.

All countries must continue climate action, even if the US under Trump reneges on its goals.

This collective effort, led by strong and committed leaders, can inspire hope and drive positive change in the fight against climate change.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT