International uncertainty that revived the Southern Seaboard Development Plan

In mid-December 2023, Thailand’s Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin delivered a speech at a roadshow for the Land Bridge project in southern Thailand, on the sidelines of the Commemorative Summit for the 50th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation in Tokyo.

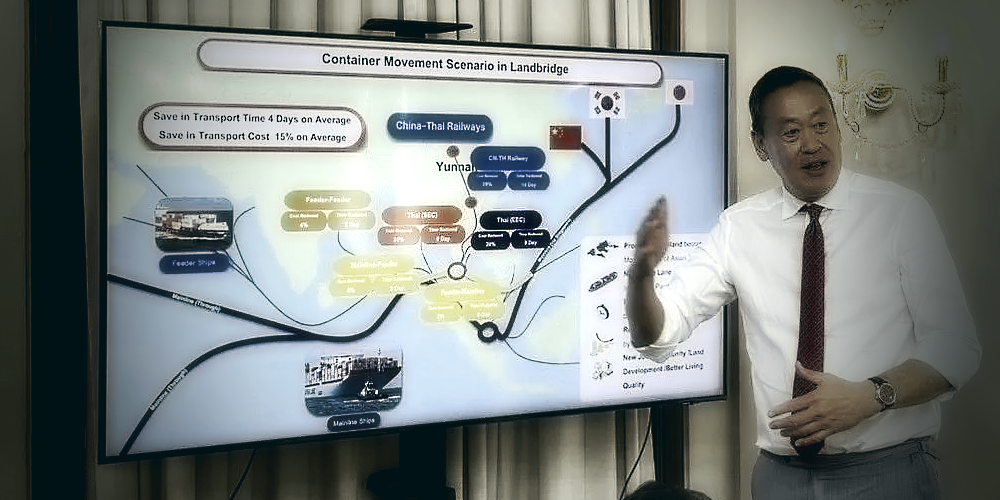

The project calls for the construction of two deep-sea ports with a combined container handling capacity of 20 million Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEUs) on the east and west coasts of the narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula.

A 90-kilometre stretch between the ports would be equipped with a six-lane highway, a double-track freight railway, and oil and natural gas pipelines, connecting the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean logistics.

The project is being promoted as a public-private partnership (PPP), with an estimated investment of 1 trillion baht (US$27.9 billion) over 15 years until 2040.

This plan did not come out of nowhere in the Srettha administration. It is an alternative to the “Kra Canal” idea, which has come and gone over and over again throughout its long history.

The concept of the Kra Canal dates back to the 17th century, during the reign of King Narai of the Ayutthaya Dynasty.

In the mid-1800s, when European powers competed to colonise Asia, France repeatedly asked the King of Thailand for permission to explore and excavate the Kra Canal.

France believed that once the canal was completed, its colony, Saigon (currently Ho Chi Minh), Vietnam, would become the most important port in Southeast Asia, surpassing British-controlled Singapore.

During World War II, the Japanese military also built a railway in the area to transport military supplies to the Burma campaign.

This region was a geopolitical strategic point for great powers such as Great Britain, France, and Japan.

The Land Bridge project is a rehash of the “Southern Seaboard Development Plan”, which was originally approved by the Chatichai Choonhavan administration at a mobile cabinet meeting in Hat Yai in 1989, but was scrapped.

Within this plan, there were proposals to establish deep-sea ports on both the east and west sides of the Malay Peninsula, connecting them by rail, highway, and pipeline.

The plan was revived by the former Prayuth administration.

The administration named the project the “Southern Economic Corridor” (SEC) and placed the Land Bridge project at the core of the SEC.

The Srettha administration, formed in coalition with the previous governing party, decided to promote the Land Bridge project in light of the shift in emphasis in international logistics from efficiency to risk diversification in the face of increasing global uncertainty.

Strait of Melaka-Singapore dependence risk

The Strait of Melaka-Singapore (SOMS) connects the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean and is a geopolitically important sea lane with the largest number of vessels in the world.

On the other hand, SOMS also has many shallow waters and rocky reefs with a depth of less than 23 metres that affect the passage of large ships.

The Singapore Strait’s narrowest channel is only 2.8 km long.

There are risks of collisions, strandings, and even piracy and armed robbery, especially at night. In the past, tanker ships attacked by pirates collided with other vessels, causing fires and oil leaks.

SOMS is predicted to exceed its transit capacity around 2030. It could be rerouted to the Sunda and Lombok straits in Indonesia, but this would require about 1.5 to 3 days of extra time and fuel.

Although the Port of Singapore boasts the world’s second-largest container handling volume, it is estimated that more than 80% of the cargo handled is transshipment cargo.

Prime Minister Srettha of Thailand claimed at the roadshow that “the Land Bridge project can reduce the number of navigational days by an average of 4 days and costs by 15%”.

The government aims to shift mainly transshipment cargoes to Thailand by providing companies and vessels with a new option to avoid SOMS.

Conditions for realising Land Bridge

For Thailand to aim to acquire transshipment cargo through the Land Bridge project, it is essential to develop the hard and soft infrastructure that supports efficient inter-modal transport.

At least at both ports, cargo handling and gate operations must be maintained 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Furthermore, most of the cargo is transit cargo that is not imported into Thailand, so it is necessary to develop an efficient bonded customs clearance and transportation system.

In the ASEAN region, the ASEAN Customs Transit System (ACTS) was launched in November 2020 with land truck transportation in mind. ACTS links online with all customs offices on the transport route, including transit countries, making it possible to cross borders through a single customs procedure.

Improvements are required so that ACTS can be used in multi-modal transportation modes such as ships, trains, and trucks, with the assumption that it will be used at the Land Bridge.

Also, if ACTS can be expanded to countries outside the ASEAN region, it will lead to expanded use of the Land Bridge.

However, in Thailand, where the political situation has been fluid in recent years, the project needs to be secured as a “Promised project not interrupted” in order to attract investors.

Previously, many long-term infrastructure projects have been cancelled with each change in government.

To avoid this, the project could be positioned as part of Thailand’s “20-year National Strategy” to raise public awareness of the importance of the infrastructure development in question, as well as to elevate the project itself to an international commitment.

The Land Bridge project is a new option for a logistics channel connecting the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean.

If it is placed in an international framework such as “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP), it will be more likely to be continued and realised.

However, this will also require the understanding of other ASEAN member states, such as Malaysia and Singapore, who will be affected by the project.

What the Thai government now urgently needs is a comprehensive strategy.

(Seiya Sukegawa is Professor at the Faculty of Political Science and Economics, Kokushikan University, Japan; and Visiting Professor, Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology, Thailand.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT