Early Chinese migrants sailed all the way here to Southeast Asia for a better living, and many were not able to return to their homeland before their lives came to an end.

As such, Chinese cemeteries set up here became the final resting place for these “wandering” souls.

Established in 1895 right in the heart of Kuala Lumpur, the Association of Kwong Tong Cemetery Management KL is where we can trace the history of early Chinese migrants in Malaya as well as how the city has evolved from a backwater village to a cosmopolitan city we have today, all through the designs and the inscriptions on tombstones found here.

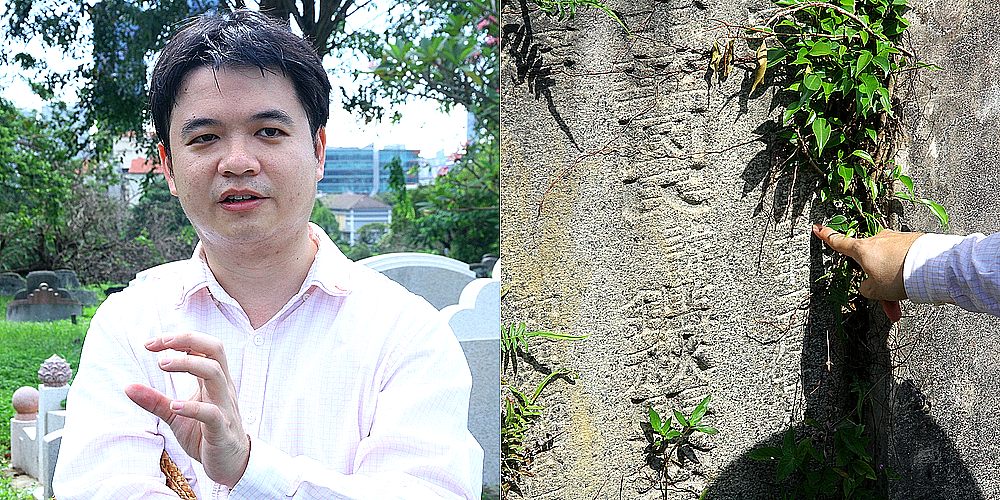

It couldn’t have been more apt for local scholar Pek Wee Chuen to call this place an open-air museum of early Chinese civilian history.

With over ten thousand tombs neatly clustered here, the cemetery not only has impressive circular tombs but also humble single-tombstone ones. Many of these tombs could be traced back to the time of utter deprivation when early Chinese migrants first arrived in Malaya.

Although official records show that the cemetery was set up in 1895, we can still find a good deal of Qing Dynasty tombs here.

Based on the year of inscription, the cemetery could have come into existence at least 11 years before the officially gazetted time of establishment.

Walking into the cemetery, one will find a diverse range of tombstone designs from Teochew to Hakka styles, which puts confusion into many.

Pek said, “Many people have got it wrong, thinking that only Cantonese people can be buried here.

“As a matter of fact, the cemetery is for the whole Guangdong province in which we have the Hakkas, Hainanese and Teochews as well, besides the Cantonese.

“So, you not only can find the tombs for Cantonese people here, but also those for the Hainanese and Hakkas.”

What’s on the face of headstone

On the front of the tombstone, one will find the name and a brief account of the departed, including the ancestral village, years of birth and death, as well as a list of children and grandchildren.

Inscriptions on the tombstone can be broadly divided into the upper, middle and lower sections.

The name of the departed appears on the middle section, typically beginning with the word 显, followed by 考 (father), 妣 (mother), 祖考 (grandfather) or 祖妣 (grandmother) to denote the relationship between the departed and the person erecting the headstone.

“If the departed has not married, the middle section will have the words 故考 instead.”

Additionally, the Chinese people are very particular about the number of words inscribed on the tombstone.

“In the past, the number of words appearing in the middle section would be adjusted for the sake of good fortune.”

The years of birth and death will appear on the left and right sides of the tombstone, while the names of posterity on the right.

The name of ancestral village can either appear on the left or right side of the tombstone, but can also be on the top section, attesting to the importance of a person’s ancestry among Chinese Malaysians.

Notably, the name of the ancestral village of the departed will typically not be inscribed on a tombstone back in China, for the simple reason that most people will be buried in the public cemetery of their own ancestral villages.

By contrast, as most early Chinese migrants here were unable to return to their home country before they died, it was utterly important to have the names of their ancestral villages inscribed on their tombs to show their sentimental attachment to their ancestry.

In general, the top section of the tombstone will mark the departed’s ancestral village, such as Jieyang and Kaiping in Guangdong province, or Quanzhou and Yongchun in Fujian province.

Some of the tombstones will instead bear the tang hao based on the ancestral family names, such as Yingchuan, Xihe, Jiangxia, Longxi and Qinghe.

Cross-cultural influences

In the Association of Kwong Tong Cemetery Management KL, we also came across tombs with the ancestry inscribed as “Shanghai, Jiangsu,” attesting to my earlier presumption that this cemetery is not exclusively for the burial of people from the Guangdong province.

Pek explained, “Shanghai was part of a larger community called San Jiang (Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Jiangxi).

“Most of the early Chinese migrants here were engaged in different trades in accordance with their ancestral communities. For instance, the Teochews were mostly fishermen, the Hainanese sold coffee and the Hokkiens were doing business.

“As for the San Jiang people, as they were better educated, they were mostly involved in education- and culture-related professions, such as running bookstores, handicraft and entertainment businesses.

“In some of the older schools here, you might find many of their pre-war principals and teachers hailing from Shanghai or Jiangsu.”

Chinese tombs are mostly shaped like a “tortoise,” and be divided into the Hokkien, Hakka, Cantonese, Teochew or Foochow styles.

The Hokkien tombs are the most typical tortoise-shaped tombs, whereby the altar for “Houtu” guardian deity is placed in front, unlike the Cantonese and Hakka tombs where the altar is placed on the left side at the back of the tomb.

Pek explained, “In Malaysia, it is not that straightforward to tell the Cantonese and Hakka tombs apart. The most popular design for a Cantonese tomb is the presence of a hat-like structure atop the tombstone.”

The shoulder of the tomb will stretch outwards to fully encircle the tomb.

“The shoulder of a Cantonese tomb will normally encircle the tomb in full, while this is not the case for a Teochew tomb.”

Another quick way of distinguishing a Teochew from a Cantonese tomb is that the Teochews will customarily start with the word 祖 on the tombstone inscription, and the name of the ancestral village will normally be omitted from the top of the tombstone.

“Some will put the name of ancestral village either on the left or right side of the headstone, but others will just leave it out altogether.”

Even if the ancestral village of a departed is Shunde, for instance, the tomb may sport a Huizhou design.

Pek explained, this is because there used to be a lot of people from Huizhou during the early days of Kuala Lumpur, hence their cultural influence over people from other ancestral villages.

Besides, the Association of Kwong Tong Cemetery Management KL also has tombs sporting various foreign styles, including nine Western-style tombs there.

This could be traced back to the era before the Opium War in China, when the Qing Dynasty opened up Guangzhou as the only port for external trade.

“Probably the Cantonese people during those years were influenced by the Western culture, hence the Western-design tombs.”

This is the second of three articles in the series of Chinese cemeteries and the traditional tomb-sweeping festival.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT