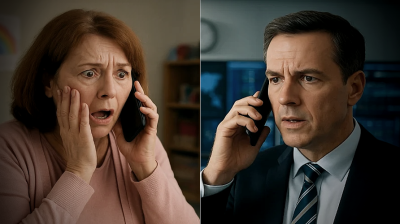

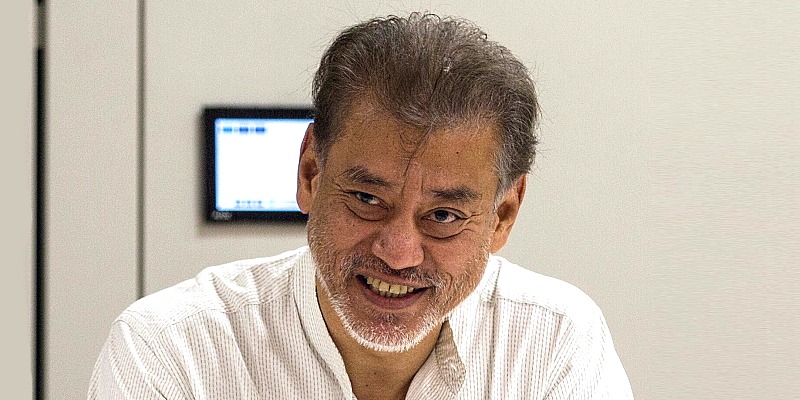

Jomo Kwame Sundaram is Senior Adviser, Khazanah Research Institute; Fellow, Academy of Science, Malaysia; and Emeritus Professor, University of Malaya.

He was UN Assistant Secretary General for Economic Development; Assistant Director General, Food and Agriculture Organization; Founder-Chair, International Development Economics Associates; and President, Malaysian Social Science Association.

He has authored and edited over a hundred books, written many academic papers, research reports, and media articles.

He received the 2007 Wassily Leontief Prize for Advancing the Frontiers of Economic Thought. In an interview to Frontline, he spoke about the impact of the Ukraine conflict on the global south.

Is the impact of the Ukraine conflict on the global economy a temporary situation or is it a crisis with deeper roots and longer term implications?

Many things can change, sometimes unexpectedly, but we may well be witnessing the beginnings of a protracted new Cold War after the US hegemony of the last three decades. Mikhail Gorbachev’s efforts to create the conditions for greater peace and international cooperation were based on a certain implicit trust. But this was betrayed with the ascendance in the 1990s of US unipolarism following the collapse of the Soviet Union and NATO expansionism despite the disappearance of its original rationale, the Soviet threat.

Multilateralism and its various post-Second World War institutions, mainly associated with the UN, continue to be undermined except when they serve US and NATO interests. Meanwhile, the sanctions against Russia and its allies have further disrupted international trade and cooperation in various ways. We live in times of militarized stagflation.

Trade liberalization largely ended as real wages declined in rich countries at the end of the 20th century. Financial globalization has nonetheless continued, with mixed consequences. Many Asian developing countries have grown even as inequalities rise in the global south. Opportunistic politicians all over have embraced ethno-populist politics, often invoking jingoist nationalist rhetoric, displacing the more progressive anti-imperialist multi-class popular fronts, or the old populism.

Reactions to the 2008-2009 global financial crisis quickly abandoned early fiscal efforts in favor of unconventional monetary policies, especially ‘quantitative easing’, an option mainly available to the US with its ‘exorbitant privilege’ of indefinitely lending by selling treasury bonds to the rest of the world, as it has done for more than half a century when Nixon ended the Bretton Woods system. Other rich economies have less policy space, leaving developing countries with even less. Much, of course, depends on developing countries’ own capacity for capital account and sovereign debt management.

Not just Europe but the global south is also affected by the conflict’s immediate consequences on the economy.

We have seen oil and gas prices rise sharply the world over following NATO’s imposition of sanctions, mainly hurting European economies, particularly those importing oil and gas from Russia. Russia has managed to get around this by offering huge discounts on its exports and increasing its reliance on the markets of China and other friendly countries. Thus, China’s alliance with Russia has been greatly strengthened. But most dangerously, we have seen the abandonment and postponement of long-promised transitions to cleaner, especially renewable, energy, thus accelerating global warming.

Just months after last year’s Glasgow promises to stop using coal, Europeans are already leading the rush back to coal as they struggle to cope with energy shortages and prices as winter approaches. Both Russia and Ukraine are major wheat suppliers. Exports have been hit, not only by sanctions but also by the mines laid in the Black Sea ports. Cereal and other food prices have also risen.

If this conflict is to eventually be a catalyst for undoing globalization, as some commentators have suggested, would that be something the global south would welcome because it could weaken the structures of global inequality? Or, should it be feared because of the disruptive economic effects that would follow?

Trade liberalization has slowed since the WTO was created in 1995. Although there is still a lot of talk about free trade agreements (FTAs), these mostly involve bilateral and plurilateral FTAs, which even free trade guru Jagdish Bhagwati has denounced as termites, undermining freer multilateral trade.

Most of FTAs today involve non-trade issues, such as investor rights and intellectual property, as in the case of the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Worse, the TPP was originally pushed by Obama as a means to surround and isolate China, but Trump withdrew, citing the danger of its investor-state dispute settlement provisions.

The closest US allies nonetheless went ahead with it, so we have the irony of the 6,350-page TPP, mainly drafted by US corporate advisers, which the US is no longer party to. Nonetheless, it poses a danger to developing country participants as powerful corporate interests have ways and means of taking advantage of it.

Overcoming Western dominance will not be easy because we have an inter-state system largely shaped by neocolonial arrangements negotiated among the big powers, especially after the Second World War. Then, there is private power. Over time, new modes of accumulating wealth have emerged, with some of it deployed to enable further capital accumulation. This happens at both national and international levels.

Western rejection at the WTO Council of the developing country-supported Indian-South African request for a TRIPS waiver during the COVID-19 pandemic reminds us of the actual exercise of such power. Collective action by the global South is unfortunately easier said than done. Hence, the choice is not really between globalization and deglobalization. In any case, this binary is not really the actual choice the world faces.

Is a new global financial architecture not based on the hegemony of the dollar a possible fallout?

Such an alternative monetary system is not only feasible, but also desirable. For instance, non-US participants at Bretton Woods in 1944 offered different proposals, of which we now know the most about Keynes’. Another possibility for change came up after President Nixon withdrew from the US’ 1944 commitments in August 1971 after the Eurodollar market undermined the greenback. With the end of the Bretton Woods system, what followed was a “non-system”.

The dollar’s position was somewhat secured after the US agreed with Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud’s collusion with OPEC partners to raise the petrol price on condition that oil and gas transactions be in dollars, giving rise to the term “petrodollars” and the belief that oil was the “new gold”. The dollar’s hegemony has since endowed the US with an ‘exorbitant privilege’, enabling it to borrow by selling bonds to the world, with buyers having little expectation of full redemption.

US and NATO sanctions against Russia, following the Ukraine invasion, have had some rather unexpected consequences. US-led efforts to exclude Russia and others from the international payments systems have forced them to consolidate alternative arrangements. They may well erode the dollar’s position as more and more economic transactions bypass the dollar, but this is unlikely to happen immediately. Already, US Fed interest rate hikes have served to strengthen the dollar.

What can developing countries do to ensure that in any emerging new world order their scope for autonomous action is enlarged?

Developing countries have had various historic opportunities to become a coherent third force, both during the Cold War and again now. From 1961, the non-aligned movement (NAM) embodied that possibility, and it became closely aligned with the G77 caucus of developing countries in the UN system. But the G77 has not been well organized, let alone institutionalized, beyond the UN segment of multilateral arrangements. And NAM has not been able to build upon or extend the Afro-Asian solidarity initiated at Bandung.

The variety of economic conditions in the global south continues to pose challenges to cooperation and solidarity. But these have not stood in the way of G77 cooperation, which has been especially clear with the G77 in New York, perhaps more than in Geneva and other UN hubs.

The creation of the WTO outside the UN system, with its own unique governance and other arrangements, has exacerbated these problems. The creation of the South Center following the South Commission’s report was expected to play a proactive role in providing analytical and policy coherence for advancing a shared vision of the global south. Sadly, this has not materialized.

If solidarity can be rebuilt and consolidated through the idea of ‘non-alignment’, it is possible for a third force to emerge and stay out of both NATO and the ‘Others’ camp, currently organized as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Only by consistently staying clear of both camps can the global south become a force to reckon with, importantly, a force for peace.

Of course, it is easier said than done, especially at a time when leadership seems wanting.

(This article was first published on Frontline by The Hindu, India.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT