While Digital Nasional Berhad (DNB) and the Ministry of Finance (MoF) still struggles to coerce the local telcos to buy into its Single Wholesale Network (SWN), the global 5G rollout continues at varying success.

And while even Malaysia’s more successful 5G-demand-driven counterparts experience hiccups on their 5G journey, DNB’s supply-driven strategy, with this backdrop, raises even more concerns.

According to GSA’s “5G-Market Snapshot,” from June 2022, 205 operators in 80 countries and territories had launched 5G mobile services, with Malaysia still cutting a lonely figure in its SWN approach to 5G rollout.

As of mid-2022, South Korea appears to be an overall leader in the global 5G rollout.

Although China and US are leading global 5G coverage, with South Korea coming up 4th in this list after China, the US, and the Philippines, according to the 5G Speedcheck Index updated on June 2022, South Korea is leading 5G race in terms of highest download speed (8 times, 11 times and 58 times faster than the US, the Philippines and China respectively).

South Korea is also among the leaders regarding 5G availability (the percentage of time users are connected to the 5G network), according to the latest OpenSignal data as of June 2022.

The above statistics makes South Korea a suitable testing ground for 5G analysis, based on which it is already possible to draw important lessons.

5G adoption among the customers seems to stall even in South Korea, and it is certainly not as enthusiastic as it was in the case of its predecessor network.

On this account, interesting comparisons were reported by Reuters on May 13, 2022. As of March 2022 (three years into 5G), the number of 5G subscribers in South Korea was just under half the number of its 4G users, while over three years into 4G rollout, the number of its users had more than doubled those of 3G.

Similarly, in the first two to three years of 4G, South Korean telcos saw their average revenue per user (ARPU) jump from 5% to 12% annually.

By contrast, very meager increases in ARPU (3.7% for KT and 0.6% for SK Telecom Co) or even decline (4.2% decline for LG Uplus Corp) from a year earlier forced South Korean telcos even to start looking into ways of diversifying their core business, to be still, able to pay off their investors. And all of this given that South Korean telcos already spent US$20 billion on boosting the connections speed by just five-fold compared to 4G. However, given the unsavory outcome numbers, they are hugely hesitant to commit resources to boost it further.

The problem that could be seen from the very beginning is now, crystal clear and summed by Kevin Loughran, wireless Chief Technology Officer for Jabil, global electronics manufacturing company: “… the investments in technology development and spectrum are by no means incremental. They lean more toward astronomical. In order to balance these investments, the user experience in 5G cannot be incremental. It needs to be disruptive.”

To create the demand, 5G requires a true “killing application.” Such killing application, by definition, must deploy the broad 5G feature spectrum.

However, even if the telcos are willing to invest heavily in the ability to provide such a broad feature set, the customers may have different strategies on how to deploy it – they may still focus on a subset of 5G features that they would purchase.

Such a “dilution” on the demand side presents a serious challenge to the overall economics of the 5G rollout. But this is for the future when most households start having numerous robots and truly connected smart homes, and the roads of our cities will be flooded with autonomous vehicles demanding grid traffic automation – the reality that is far away even for South Korea.

As of now, the majority of Malaysia’s households save every spare cent to be able to put food on their tables. Therefore, they are likely to find it even more difficult than the South Koreans to justify an extra monthly outlay for a five-fold increase in their mobile Internet speed.

If an average mobile Internet user is not fully utilizing even the potential of 4G anyway, the question arises: is it not logical to focus the efforts on roadblocks to a faster 4G — the network really needed here and now — by upgrading the network, increasing national fiberisation (focus on the backhaul, lack of which, is the main cause for the lack of the progress for Malaysia’s broadband expansion, according to Dr Mohamed Awang Lah), and repurposing or releasing an additional spectrum?

Reading Jendela’s Q1 2022 report, which, Dr Mohamed Awang Lah insists, is still “service provider-centric report, not end-users’,” Malaysia’s 4G population coverage is “on track,” increased to 95.5% in Q1 2022, and is well poised to achieve its 96.9% populated area coverage target by the end of 2022.

In addition, the average mobile broadband speed has increased to 40.13 Mbps, surpassing the original Phase 1 target of 35 Mbps.

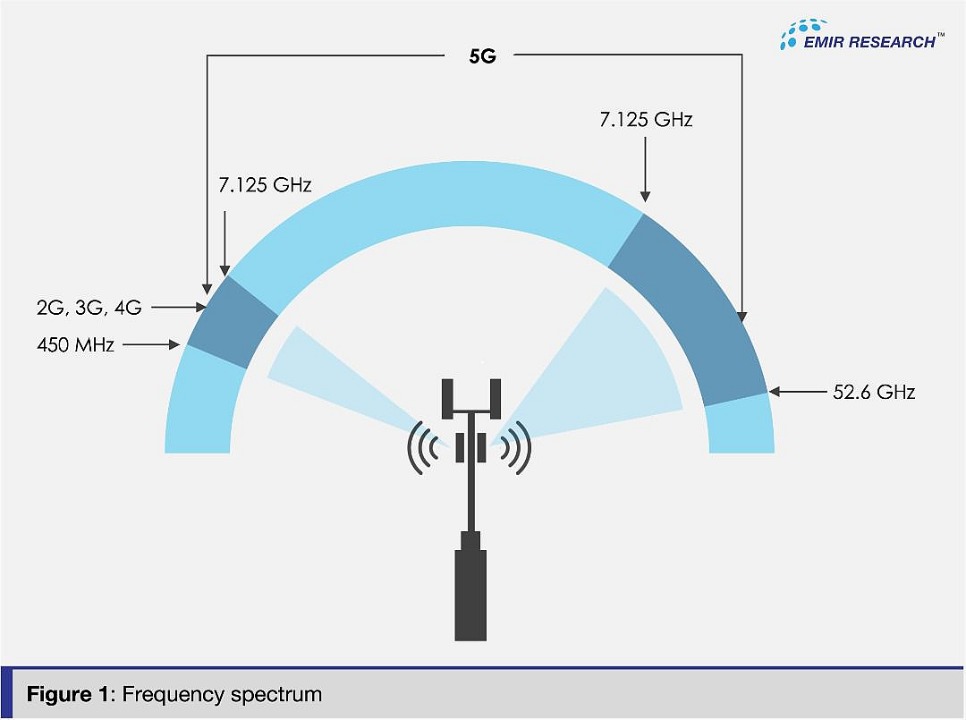

In addition, this report states that the 3G spectrum is almost completely retired. Therefore, we could consider repurposing it to increase the 4G frequency band. And, if the government could reconsider assigning sub-6 GHz band to telcos rather than DNB, this would not only allow them to organically (based on demand) rollout 5G at globally comparable costs but also simultaneously speed up their 4G networks by extending their 4G frequency band even wider (See Figure 1).

Meanwhile, DNB as a government-led entity should solely focus its efforts on sharing the passive infrastructure, especially, the backhaul link (one of the highest-cost in infrastructure) to enable last mile competition. Now, this is the approach that will reap significant benefits to the end users.

Therefore, it is timely to ask again how all the above stands against DNB’s projected costs, supply-driven approach, ambitious coverage targets and over-arching official choreographed “narrative” objective? And most importantly, who will make up for the potential losses encountered?

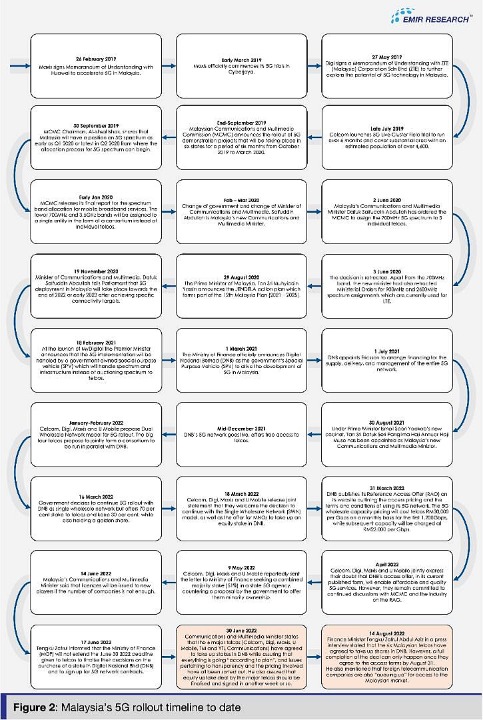

Not surprising, we see no progress from where the issue of major telcos taking up a stake in DNB’s SWN since end of June 2022 (See Figure 2) when the Communications and Multimedia Minister assured the public that the equity uptake deal by the major telcos should be finalized and signed in another week or so.

However, one and a half months later, on August 14, 2022, the Finance Minister Tengku Zafrul’s press statement implied that some of the major telcos have yet to agree to the Reference Access Offer (RAO) terms, although they have agreed to take up the stake in DNB as offered by the government.

The finance minister further emphasized the set deadline is August 31, 2022 for the telcos to sign up and that foreign international companies are “queuing up” for the access to Malaysian market.

The Finance Minister added that it is very hard not to allow foreign players into the Malaysian market considering the potential for lower consumer prices.

However, the believe that DNB’s RAO terms are “not commercially viable” and likely to lead to higher customer costs and slower adoption rates is precisely one of the main points of contention between the local telcos and DNB apart from the refusal to become a “passive shareholder” with restrictive terms.

And if the RAO terms are not commercially viable even for the local telcos who operates in a Ringgit Malaysia environment, margins for the foreign telcos could be further squeezed due to a very weak ringgit making it absolutely not clear how this can be translated into a lower prices for Malaysian consumers.

Nevertheless, the deadline is here and gone. And two of Malaysia’s largest telcos have just reportedly declined to take up stake in DNB even though they are still open to continue discussing how to make “not commercially viable” RAO, commercially viable.

Here lies another problem, DNB and MoF reportedly dished out another dateline i.e. September 30, 2022 for the access agreement for the local telcos. This, despite the absence of regulatory framework for the 5G Access Agreement as MCMC has yet to release the framework covering areas like Service Level Agreement (SLA), pricing etc. Apparently it will be ready only in December 2022. Sign first, framework later.

We could foresee that this may trigger other local and foreign telcos, including those who have stake in local carriers, to question the reasons for such a refusal.

No foreign telco or investor will sign up for DNB equity under present conditions, unless MoF underwrites the risks.

It is important to note logically, that the 4 telcos that signed up earlier to take up the stake, will have to revert to their respective Boards, as it was previously at RM200 million per telco equity investment instead of RM300 million now, given two telcos have reportedly declined, given the total offer of equity investment at RM1.2 billion for 70%.

Forget not Telenor with a substantial shareholding (49%) in Digi, who is known for their good governance and integrity with impeccable transparency will start asking serious questions.

And past the deadline, Malaysian public is beyond excited to see which foreign telcos take up the stake in DNB. Foreign telcos have higher standards of governance and integrity with wholesome transparency and cannot be dictated by whims or fancies of political masters or unreasonable deadlines.

They normally have higher and stringent levels of due diligence and what more if they are from a developed nation. Unless it is “North Korea Telecoms.”

So, the DNB saga will be a never-ending story with never-ending deadlines. 6G is in trials now, and even before the waves of 5G settles in Malaysia, 6G will start its roll-out elsewhere.

(Dr. Rais Hussin is the CEO of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT