In May this year, the first conservative government in five years was inaugurated in South Korea.

It has designated North Korea as its “main enemy” and attaches great importance to the US-South Korea alliance while also agreeing at the Japan-US-South Trilateral Ministerial Meeting in June to conduct Pacific Dragon, a drill for detecting and tracking North Korean ballistic missiles.

Large-scale US-South Korea Joint Military Exercises are scheduled for late August.

As an antithesis to former President Moon Jae-in who sought to appease North Korea, President Yoon Suk-yeol has been in high spirits since taking office.

However, those high spirits could also be termed mere bravado. Not only is his approval rating plummeting due to high prices and poor personnel decisions, but his ruling party is also a minority in the National Assembly, and unless there is a major political reorganization before the next general election in April 2024, he will not be able to implement the policies he seeks.

We also must not forget that the presidential election was won by the narrow margin of just 0.73%, with half of the South Korean public opinion remaining progressive.

The North Koreans are also aware of Yoon Suk-yeol’s weaknesses. Unlike five years ago when they were striving to develop an ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile) against the United States, they are currently investing in the development of hypersonic and other short-range missiles that are difficult to intercept, while increasingly intimidating South Korea, having defined them as their “enemy.”

Moreover, the long-held claim that nuclear weapons are a deterrence has been overturned as they have recently come to “have a second mission” with the threat of preemptive use of nuclear weapons.

Successive South Korean conservative governments have formulated “decapitation operations” against North Korea’s supreme leader, and Pyongyang’s stance now is that it might resort to a nuclear attack on South Korea if Yoon Suk-yeol were to show indications of this.

The atmosphere of wanting dialogue that existed between 2018 and 2019 has already become a thing of the past, and both US-North Korea and inter-Korean relations have long since reached an impasse.

South Korea’s defense spending has come to exceed that of Japan, and the two Koreas have fully entered an era of a military expansion race.

In late June, the Enlarged Meeting of the Central Military Commission of the Workers’ Party of Korea was held, and General Secretary Kim Jong-un spent three days to decide on personnel appointments and present a military policy.

Kim Jong-un emphasized the need to “consolidate in every way the powerful self-defense capabilities for overwhelming any hostile forces and thus reliably protect the dignity of the great country and the security of its great people”.

But the specifics of his instructions were not made public and there was no mention of nuclear testing.

In other words, although he sent a firm message to the United States and South Korea, he did not show his cards.

This represents a change in North Korea’s military policy. Whenever North Korea has conducted a missile test, it has put its military power on display by announcing in detail the type, range, and altitude of the missile. It may have thought that this would deter the United States and South Korea.

However, since May this year, missiles have been launched without any reporting, as an eerie silence has been kept.

By concealing its weapons development, it appears that it has shifted to an approach of shaking up the United States and South Korea.

You could say that this is a form of rational judgement on their side.

The reason why the country has been announcing their development of nuclear missiles in detail is because it has also kept in mind that negotiations with the United States would proceed on that basis, but the Biden administration has its hands full with domestic COVID-19 countermeasures, the situation in Ukraine, and the confrontation between the United States and China, so it has not shown any signs that they have the capacity to restart US-North Korea negotiations. If so, there would be no point in North Korea showing their cards.

A former prosecutor, Yoon Suk-yeol had no political or diplomatic experience before becoming president, so we should assume that his advisers have quite a lot of say.

The current diplomats are more or less the same line-up as the brains of former President Lee Myung-bak, and their policies toward North Korea are similar.

The Lee Myung-bak administration (2008–2013) advocated “Vision 3000: Denuclearization and Openness,” which included a support measure to ensure an income of $3,000 per capita if North Korea pursues denuclearization.

But North Korea ignored this “condescending” proposal, instead taking the lives of 46 South Koreans through the sinking of the ROKS Cheonan in March 2010 and then another four with the bombardment of Yeonpyeong in November.

This was during the era of the Kim Jong-il administration, but the prevailing view is that the orders came from Kim Jong-un, who had just been nominated as his successor.

The Lee Myung-bak administration brought huge amounts of foreign currency to North Korea through the Kaesong Industrial Region. Without ever being able to hold an inter-Korean summit, it unilaterally suffered the loss of life.

A decade onward, and North Korea has repeatedly conducted nuclear and missile tests, and its military power has only increased.

Under these circumstances, there are worries that the Kim Jong-un administration might once again launch military provocations against South Korea.

If North Korea engages in provocative acts, Japan, the United States and South Korea will unite to exert further pressure, but the issue is that this will not present any major inconvenience for North Korea, unwilling to engage in dialogue for the time being.

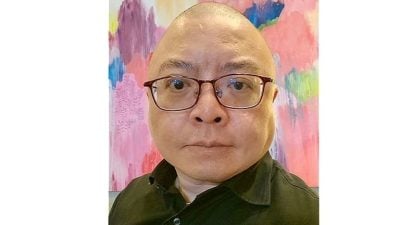

(Atsuhito Isozaki is Professor at Keio University, Japan.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT