JAKARTA: For 30 years, Indonesian artist Agus Suwage has created hyper-stylised selfies — from caricatures of himself to imposing his face on a dictator — to document his search for identity in the turmoil of the country’s recent history.

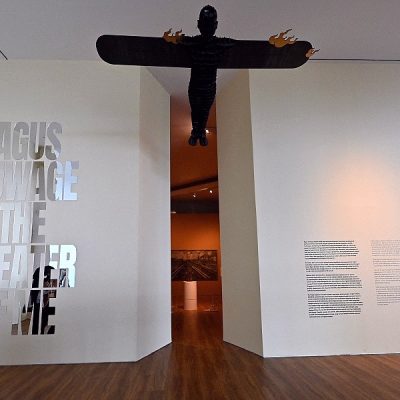

The Macan Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Jakarta is devoting an exhibition — “The Theatre of Me” — to the work of the artist with more than 80 pieces on display spanning three decades of his career.

Suwage’s self-portraits document his life as an artist deeply influenced by political change in Indonesia, such as the fall of dictator Suharto’s regime in 1998 and the hopes raised by the democratic revival that followed.

The 63-year-old depicts himself in unconventional ways and his unnerving installations play with racial and cultural stereotypes in the Southeast Asian archipelago.

The exhibition has been on hold for several years after being postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic, which closed museums for months.

“During this long hiatus, I had forgotten a lot of the process and the artworks we planned to exhibit. So this is an important moment of rediscovering, reminiscing and rekindling the works I’ve done — just like meeting an old friend,” Suwage told reporters.

One of the works, “Self-Portrait and the Theatre Stage”, has never been shown until now.

Dozens of ironic or grotesque versions of the artist’s head adorn a large wall — in flames, like a bird, a pitbull or a kettle — to create a cynical, visual commentary on the many different faces of politics.

In Suwage’s work, “the self-portrait came from the beginning,” Aaron Seeto, director of the Macan Museum, told reporters.

“He began making self-portraits firstly because he believes that one must be self-critical before you criticise others, and also there was an economic pragmatism about it, he would use his own body and wouldn’t have to pay models,” he said.

Agents in a cage

Suwage’s later installations give pride of place to dark humour, and their provocative nature increasingly tests the tolerance of the public in the country with the largest Muslim population in the world.

In one, a skeleton sits in a bathtub of rice (“Luxury Crime”), in others a pyramid of one thousand beer bottles is topped by a “guardian angel” skeleton and a statue of a half-naked Frida Kahlo hangs on the cross, her body pierced by arrows.

The Suharto regime forced the artist, from a Chinese-Indonesian merchant family in Central Java, to adopt a more Indonesian-sounding name in 1967 from his birth name of Oei Hok Sioe.

Suwage went on to study graphic art in the Indonesian city of Bandung where a photographer roommate captured the images he would use as the basis of his early self-portraits.

At the end of the 1990s he lived through the repression of student movements and deadly riots in Jakarta, a period that would shape his development as an artist.

After experiencing success around the world — his works can be found in museums from Japan to the United States — and seeing the price of his pieces soar, Suwage is not shy to criticise the art market.

In the “Toys ‘S’ US” series from 2003, he miniaturises himself as a wire toy in various forms to explore the relationship between artist and collector, and how he felt infantilised and forced to work by those around him in the art scene.

In his “Passion Play” installation, he puts life-size mannequins representing his collectors and agents in a large cage.

“Through this process of reflection since my beginnings as an artist, I have seen a close relationship between art, politics and society,” Suwage said.

It is an “exploration of memory, fear, alienation, dreams, identity and humour.”

The exhibition runs until mid-October.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT