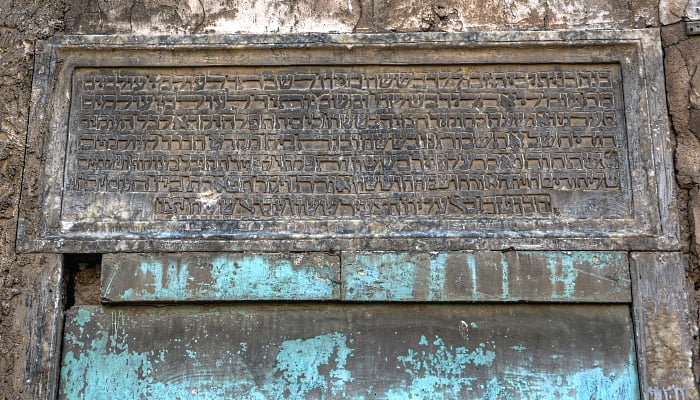

BAGHDAD: In a busy district of the Iraqi capital Baghdad, there is little to distinguish the faded brick building, except for a Hebrew inscription above the entrance.

Iraq’s Jewish community was once one of the largest in the Middle East but its members have dwindled to a handful, outside of the autonomous Kurdistan region.

“Our heritage is in a pitiful condition” and authorities take no notice, said a member of the congregation who requested anonymity, fearing reprisals.

Their precious history, including the synagogue, is threatened in a country torn apart by decades of war, corruption and armed groups.

While historical treasures ruined by jihadists are being restored in Iraq, rare international efforts at saving the Jewish heritage have not been enough.

Baghdad’s Meir Tweig Synagogue, built in 1942, seems to have been frozen in time.

Behind its padlocked doors, the benches are covered in white cloth to shield them from the sun. The walls of the sky-blue two-storey columned interior are crumbling.

The steps leading to a wooden cabinet holding the sacred Sefer Torah scrolls are coming apart.

Flanked by marble plaques engraved with seven-branched candelabra and psalms, the cabinet shelters the scrolls written in hand calligraphy on gazelle leather.

“We used to pray here,” the member said. “We celebrated our festivals, and in summer we studied religious courses in Hebrew.”

One synagogue in Iraq’s south has been illegally occupied and turned into a warehouse, the woman added.

“Save this heritage,” she said, asking for the United Nations’ help.

Deep roots

Jewish roots in Iraq go back about 2,600 years, on the land where the patriarch Abraham was born and where they wrote the Babylonian Talmud.

More than 2,500 years later, in Ottoman-ruled Baghdad, Jews made up 40 percent of city inhabitants.

By the time of Israel’s creation in 1948 they numbered 150,000, but three years later, 96 percent of the community had left.

A report published in 2020 listed Jewish heritage sites in Iraq and Syria, some dating back to the first millennium BC.

The study identified 118 synagogues, 48 schools, nine sanctuaries and three cemeteries among the Iraqi Jewish heritage sites. Most are now gone.

“In Iraq, only 30 of the 297 documented sites are confirmed to still exist,” according to the report published by the London-based Foundation for Jewish Heritage and ASOR, the non-profit American Society of Overseas Research.

“Of these 30 sites, 21 are in poor or very bad condition,” it added.

The few remaining Jews in Iraq “worked very hard to protect and preserve their heritage, but the scale of the work was beyond their abilities,” said Darren Ashby, who worked on the study.

“Over time, much of this heritage was lost to seizure, sale or slow decay and collapse,” said Ashby, from the University of Pennsylvania’s Iraq Heritage Stabilization Program.

Glimmers of hope

In Mosul, Iraq’s second city and a melting pot of diverse ethnic and religious communities, colourful paintings signal the ruins of the Sasson synagogue at a bend in an alley.

The synagogue’s collapsed ceiling vault exposes arches and stone columns. But all around is rubble, scrap metal and dumped rubbish.

A local official in charge of antiquities, Mossaab Mohammed Jassem, said the 17th-century building had “served as a residence for a long time.”

He said it belongs to a local family which holds the ownership title, and asked the local authorities to either buy it from them or restore it.

Aliph, the Swiss-based International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas, has expressed its willingness to support a potential renovation project of the Sasson synagogue.

There have been other glimmers of hope.

In January, the United States consulate in Arbil, capital of the Kurdish region which did not experience the same level of internecine violence, announced $500,000 in funding to restore the small Ezekiel synagogue near Akre.

Even though some had converted to Islam, other families of Jewish descent live in the Kurdish zone.

US funds also helped restore the tomb of Nahum, one of Judaism’s minor prophets, along with financial support from Kurdistan and private donors.

Surrounded by church steeples in the village of Al-Qosh, the stone sanctuary now looks almost new. Built under its actual form in the 18th century, it could date back to the 10th century, according to local officials.

Joseph Elias Yalda, an official from Al-Qosh heritage museum, remembers stories told by local elders, who said Jewish pilgrims would pour in for a week each June to pray.

“They came from all the provinces and even from neighbouring countries,” said Yalda, who is in his sixties.

“After the religious commemoration, there was a celebration in the old town, with drinking and dancing.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT