By Marion THIBAUT

AMOS, Canada (AFP) — Jimmy Papatie, just five years old, clutched at his grandmother’s skirt, his face bathed in tears. He did not want to get on the bus. He did not want to be sent away from his family, and the Canadian forest where his Algonquin tribe lived.

But a police officer shoved his grandmother and grabbed the child. A few minutes later, he was herded onto the bus with other Indigenous children, and the vehicle pulled out, their screams and sobs still resonating.

It was 1969, and Papatie’s life changed forever.

He was taken to a boarding school for Indigenous children at Saint-Marc-de-Figuery, not far from his family home, in an area 600 kilometers north of Montreal. Papatie would stay there until the school shut down four years later.

“We didn’t know where we were going. We didn’t know what was going to happen to us. In just a few hours, we were completely uprooted — linguistically, culturally, spiritually,” Papatie, now 57, told AFP at a restaurant near the former school site.

He is just one of about 150,000 Indigenous children who were ripped from their families and placed in 139 schools meant to forcibly assimilate them into Canadian “culture” — in other words, strip them of their native traditions.

Thousands of students died, mostly from malnutrition, disease or neglect, in what a truth and reconciliation committee called “cultural genocide” in a 2015 report. Many others were physically or sexually abused.

On the heels of the discovery of more than 1,200 unmarked graves at these schools, Canada is finally starting to come to terms with the nationwide trauma — and for thousands of people like Papatie, the reckoning is reopening old, deep wounds.

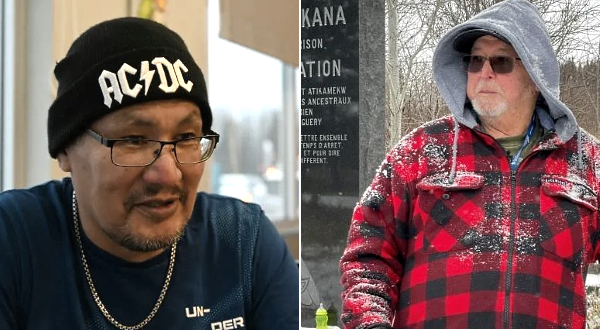

But Papatie — a former tribal leader whose hair is now cut short, his forearms covered in tattoos — says he’s ready to talk openly about the “terrible” things he endured decades ago.

‘Dirty Indians’

Once Papatie arrived at the school in Quebec province on that life-changing day in 1969, he recalled, he realized his world had been upended — on government orders.

The children’s hair, traditionally worn long, was cut short. They were told they were “dirty Indians” and scrubbed with a hard brush. Their beaded moccasins and moose hide jackets — usual clothing for the Algonquin — were replaced with uniforms.

Teachers and other staff spoke to the kids in French, a language they did not understand. Their native language was banned.

And then, the ultimate indignity came at day’s end: their names were taken away. From that point on, they were referred to by number.

“At the school, I had no name, I was number 70,” Fred Kistabish says.

He often returns to the site of the Saint-Marc-de-Figuery school, where he lived for a decade. A small memorial is now there, with black and white photos of past students. Dozens of tiny pairs of shoes have been placed there to honor the dead.

“This is where I became someone else,” the 77-year-old recalls, walking with the aid of a cane over the few stones that remain of the school, now covered in weeds and a light dusting of snow as winter sets in.

Until the 1980s, these schools — first opened in the mid-19th century — were one of the cornerstones of the government’s policy to assimilate Indigenous peoples, who today represent nearly five percent of Canada’s population.

At the start of each school year, a government official tasked with liaising with Indigenous peoples — accompanied by police officers — would make the rounds, gathering up children from the largely nomadic communities.

The schools had a mission: educate them, convert them, assimilate them.

But Kistabish says he resisted: “They did not completely succeed in changing me.”

‘Hardest moments of my life’

For Kistabish, the former chief of the Pikogan reserve, the hardest thing about living at the school was being able to see his sisters — and not being allowed to speak to them.

“When they saw me in the cafeteria, they cried… that was hard,” he recalls.

That sense of being totally isolated, even when still near loved ones, was also a searing blow for Alice Mowatt, who lived at Saint-Marc-de-Figuery from age six to age 13.

Years later, she said she recorded her memories of that time in small notebooks, to be sure “not to forget” and also to “free” herself from the years of suffering.

In one notebook, she describes her arrival at the school: “I don’t remember how I ended up at the school. I suppose I followed my sisters. But once I was there, they divided us by age group, and then I realized I was going to be alone.

“At that moment, I was six years old, and I didn’t know a word of French. Those were the hardest moments of my life,” the 73-year-old former librarian with long gray hair recounts.

In her kitchen, every object in sight, even each utensil, has a sticker on it with its name in Anishinaabe, her native language.

“This is for my grandchildren, so that they retain a few words of our language,” she says.

Many students at the schools completely lost their Indigenous languages; some remained mute for months.

Speaking anything but French or English meant certain punishment: a few smacks of a ruler or a belt, a mouth washed out with soap or even days locked in a closet.

“If you were talking when you shouldn’t, if you didn’t line up fast enough, if you didn’t get out of bed quickly enough… I think they had 50 million excuses why they should strap you,” explains Dawn Hill, who is now 72.

The retired teacher, with short white hair and rectangular glasses, spent time in a school in Brantford, south of Toronto.

When she thinks about that time in her life, her eyes glaze over and she stares ahead blankly.

“It was kind of like a dog-eat-dog world. There was always an element of fear in your surroundings. You never felt safe,” she told AFP.

The institution, located in a remote spot at the end of a long lane lined with maple trees, was run by the Anglican church. It was one of the first to be opened in Canada. Now, authorities have begun hunting for unmarked graves on the property.

Slow national reckoning

Brantford is not the only location where such searches are ongoing.

In the wake of this year’s discovery of more than 1,200 unmarked graves, archaeologists are working at numerous sites to find the remains of what authorities believe may be 4,000 to 6,000 children who disappeared at the schools.

Thousands of survivors shared horrific accounts of life in the Indigenous boarding schools before the truth and reconciliation committee, which was formed in 2008 to analyze a policy that was said to seek to “kill the Indian in the child.”

Mowatt was one of them, testifying about the sexual abuse she suffered — the first time she had told anyone about it.

After seven years of investigation and thousands of interviews, the commission released its report about a time in history that is little understood by most Canadians — and issued its seminal 2015 report about “cultural genocide.”

“The stories of that experience are sometimes difficult to accept as something that could have happened in a country such as Canada, which has long prided itself on being a bastion of democracy, peace, and kindness throughout the world,” it said.

“Children were abused, physically and sexually, and they died in the schools in numbers that would not have been tolerated in any school system anywhere in the country, or in the world,” added the report, which was more than 500 pages.

On an official level, Canada has slowly lifted the veil on this historical tragedy.

In 2008, then Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper offered an apology. Current Prime Minister Justin Trudeau did the same in 2015, the year the committee released its report.

‘They stole my youth’

More recently, the Catholic Church has admitted its role in the suffering endured by members of First Nations communities, as the church ran many of the country’s residential schools.

Next year, for the first time, a delegation of representatives from Indigenous groups will go to the Vatican before an expected visit to Canada by Pope Francis.

“I want the pope to apologize to us, the survivors of these schools. It will take a day or two to meet with us, but he must take that time, and after that, we can turn the page,” says Oscar Kistabish, 75, who also lived at Saint-Marc-de-Figuery.

Kistabish, who is not related to Fred, describes himself as a “survivor.”

“They stole my youth from me,” said the broad-shouldered man, his long dark hair tied back.

For the first months after his arrival at the boarding school, Kistabish says he was often sick because of the change in diet but also from fear. He does note there were fleeting moments of “fun” when he discovered ice hockey with his classmates.

“I learned not to have any emotions,” he says bitterly, explaining that — like many others who spent time in the institutions — he turned to alcohol to cope, leading to problems in his adult life.

For Marie-Pierre Bosquet, an anthropologist at the University of Montreal, the entire Indigenous school system “generated so much trauma in Indigenous communities, passed from generation to generation.”

“No one talked about what happened to them, but everyone knew what it meant when one of the priests came to get you out of bed,” Papatie recalls. It took him 45 years to talk about being a victim of rape.

In all, more than 38,000 claims of serious sexual and physical abuse have been registered by the truth and reconciliation committee. On the flip side, Canadian courts have delivered less than 50 guilty verdicts related to those accusations.

Reflecting on the “demons” that haunted him for years, Papatie describes his adult life as a series of downfalls: alcohol, drugs, suicide attempts and violence.

“It took me until I was more than 50 years old and two rounds of therapy to be able to sleep with the lights off, to be able to undress myself in front of a woman, to have a successful intimate moment with someone,” he says.

“Today, I am no longer in hiding. But I also know that doesn’t excuse the pain I have caused others,” he added, admitting he himself committed sexual assault.

Many “haven’t recovered and haven’t moved on and haven’t dealt with it,” says Hill, who is still angry that those responsible for her pain were never prosecuted.

“We were just children…”

‘What is our national history?’

The recent discovery of the unmarked graves seems to have signaled to Canada it was time to reckon with the past. “Reconciliation” is a national buzzword.

The country is not alone: similar efforts to make amends for wrongs

committed against minorities are taking place in other parts of the world.

In Scandinavia, Norway, Finland and Sweden recently set up truth commissions tasked with investigating the persecution of the Sami people.

Elsewhere, young people are primarily the driving force behind initiatives undertaken to sensitize people to the crimes of the past, as a way to better understand diversity in today’s society.

“This is not the image that Canadians have of their country. Today, they are asking themselves, ‘In the end, what are the foundations of our country? What is our national history?'” Bousquet notes, calling the tragedy a shock to the system for her compatriots.

“Until now, they saw themselves as a big multicultural democracy, with a glorious past, and vast open spaces — not as a country built on a genocide.”

Researchers agree that finding the unmarked graves was a major turning point.

“It’s as if with this evidence, it suddenly became concrete, real,” added Bousquet, who is the director of the Indigenous studies program at the University of Montreal.

But for Sebastien Brodeur-Girard, who teaches at the School of Indigenous Studies at the University of Quebec, “there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure a true understanding of this episode in history and its lasting consequences.”

In late September, on the first-ever National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, Trudeau said: “Until we understand as a country that each one of our stories is all of our story, there cannot be truth, there cannot be reconciliation.”

Today, many Indigenous peoples still live in poverty and racism endures, experts say.

First Nations peoples did not win the right to vote in Canada until 1960, and in some provinces like Quebec, that right did not come until 1969.

Last year, the United Nations denounced the wide range of problems faced by Indigenous peoples, from a lack of clean drinking water, to discrimination against children living on reservations to over-representation in prisons.

“The government and the Church think that saying sorry will be enough,” says Papatie.

“While all that may be sincere, they really should put money on the table — reparations. I know what it would cost to rebuild a broken individual, so for an entire community…” he said, trailing off.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT