By Joshua MELVIN

GREEN BANK — Yvonne Wallech loves the digital respite and sense of community in her tiny US town, where cell phone service is effectively barred and outsiders come seeking the shelter of that quiet.

She has internet at her property in Green Bank, West Virginia but as soon as she leaves home — and is not on someone else’s connection — there are no pings, dings or rings.

“Coming here and being able — if you want — to get away from it (internet), there is a certain cleansing that comes to you, that gives you time to clear your mind,” the 59-year-old owner of a gift shop told AFP.

But Green Bank is changing: Wifi is officially discouraged but has become common, property values are climbing and not everyone agrees about what comes next for this seeming digital age refuge that is fraught with complexity.

Despite its population of under 200 people and remote location among rolling hills, dense forests and farms about four hours’ drive from the US capital Washington, it is a place of international fascination.

That’s because it is home to the over six-decade-old Green Bank Observatory, which requires radio silence to be able to peer deep into space to observe stars and black holes.

To protect the observatory’s work, as well as the operations of a nearby spy installation, the US government created the National Radio Quiet Zone in 1958.

The zone imposes limits and oversight on man made radio waves in the 13,000 square miles (almost 34,000 square kilometers) that surround Green Bank, where restrictions are officially supposed to be tightest on electronic noise makers like WiFi routers.

Locals said wireless internet has become widespread in recent years and that they hadn’t faced any sanctions, despite rules that technically allow violators to be fined $50.

Even before WiFi’s proliferation, locals got their dose of Netflix or Facebook via hardwired internet connections, yet cell service has remained non-existent under the rules.

‘A quieter zone’

West Virginia state tourism officials promote this quirk of the area as the “ultimate digital detox”.

“In a world today where we can never go more than a minute or two without hearing the beep or the buzz of a technology device, it is the place you can go to get away from all of this,” said Chelsea Ruby, the state’s secretary of tourism.

It’s a pitch that resonates in the United States, where Pew Research data shows 85 percent of US adults say they have a smartphone and nearly a third report they are “almost constantly” online.

While visiting Green Bank Observatory, tourist Nancy Showalter was surprised to learn why her phone couldn’t get a signal, but she also said she had quickly come to like the silence.

“You visit, you listen to other people,” said the 78-year-old from Indiana.

“I think it’s wonderful. I think more people should do it.”

Not everyone agrees, of course. Green Bank native Patrick Coleman, 69, argued that the lack of cell service is dangerous and needs to end.

“People that live in this area are denied a safety net,” the bed and breakfast owner said, adding a car accident in a remote area could become very serious without the ability to call for help.

He also noted cell service is already available at nearby Snowshoe ski resort, a key economic driver locally that draws floods of tourists in the snowy months.

As the resort has grown to include high-end lodging, restaurants and shops, property values in surrounding Pocahontas County have by some measures increased at almost triple the national rate over the past decade.

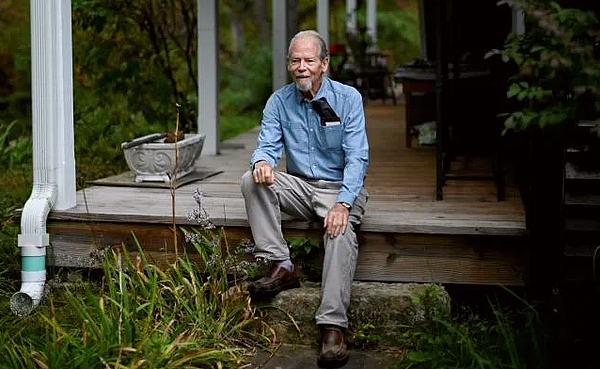

“They may very well want to get a Walmart right here and Kroger’s right here and all the things that they’ve spent their life being used to,” said long-time local George Deike, referring to the influx of outsiders.

“I don’t know whether the whole world has to be like that,” added Deike, who runs an equestrian retreat.

Recent arrival Ned Dougherty came to Green Bank because he was intrigued by its less-connected lifestyle that he had read about in press reports.

“I came here hoping for a quieter zone, a place without WiFi,” the 38-year-old teacher said. “Everybody wishes this was the Shangri La of quiet.”

But he noted there’s a more direct way to get control of one’s digital life.

“I don’t have to use my phone, no matter where I live,” he said. “It’s not solved by arriving in a zip code. If I want to turn off, I have to do it myself… And I think we all know we should.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT