By Amaury HAUCHARD

INGALL, Niger (AFP) — Ten-year-old Moussa will bask in the glory of the weekend camel race in Niger for a long time. Little higher than his victorious charger’s knees, the boy fairly flew across the desert to snatch first prize in one of the most prestigious events of the Sahara.

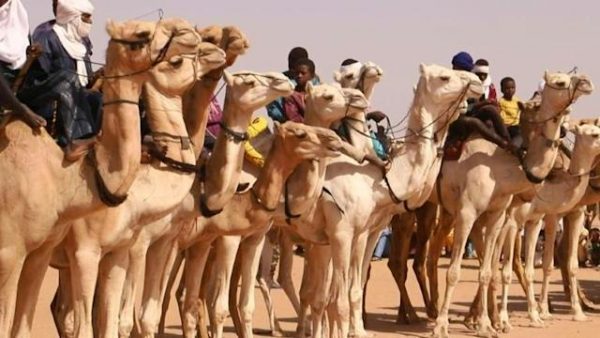

The competition drew racing camels from across Niger — and further afield — to the oasis town of Ingall, the country’s traditional gateway to the Sahara and scene of the annual Cure Salee gathering of Tuareg and Wodaabe nomads.

But it was Moussa — more used to long, hot days tending his father’s cattle in the desert — who won Saturday’s big race.

Moussa does not go to school but has been riding camels, cantankerous beasts that roar, snort and spit foul-smelling bile at their enemies, since he was three years old. At seven, he says, he began venturing out solo. “I used to be afraid to ride camels alone,” he says.

Now one metre (three foot three inches) tall, Moussa is dreaming of a golden future in which he will have “plenty of camels” and above all “will win other races”.

The race is a highlight of the three-day nomad festival, when far-flung herders lead their cattle from up to 400 kilometres (250 miles) away, converging on three springs of water rich in mineral salts that give the gathering its name.

Music and marriages

The celebration comes after the rains in mid-September, with music and ritual dances, courtship and weddings and vaccinations for beasts and their masters, bringing relief from the nomads’ increasingly hard lives — marginalized and trapped in a region riven by jihadist violence.

For this brief respite, people prefer not to talk about their troubles but to just have fun.

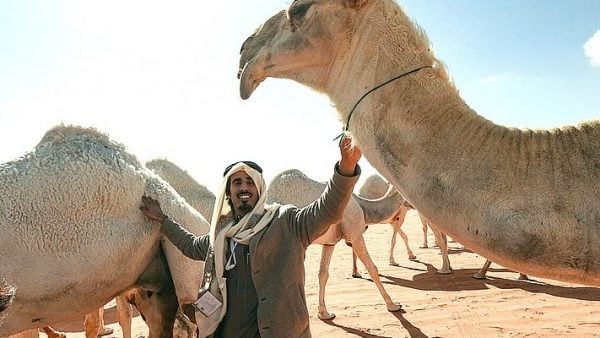

“There is football in Europe, here we have camel racing,” says Khamid Ekwel, a renowned owner of racing camels.

So at dawn on Saturday, hundreds of herders pushed against the barriers of the stadium — a track of five kilometres (three miles) in the desert marked out by stones painted white — to watch the race over two laps.

Dozens of pick-ups are strategically parked to give spectators standing on their roofs the best view. Others have brought their camels — around two metres at the shoulder — to gain a little height. Everyone waits under the sun rising in a blue sky, betting on the 25 animals in the race.

The camels soon arrive and are placed behind a green rope stretched across the starting line. The jockeys are young — for the lighter they are, the faster the beasts will go.

Lahsanne Abdallah Najim, a race official and himself owner of one of the favorites, is stressed: he must ensure an orderly start, but at the same time wants his animal to win.

The big moment is here. Najim gets into his pick-up, signals to about 15 people to climb in the back, readjusts his scarf on his nose, then clamps down his brakes while waiting for the white flag.

The flag drops. The camels head off at a gallop. The spectators shout. Najim’s vehicle and a dozen others roar off, kicking up a sandstorm. Soon, we can’t see much, the animals are already far ahead.

‘A winning camel’

In his car, Najim smiles: “There are some who choose speed now, but they will be last in the end. It’s on the second lap that you need to accelerate.”

After the first five kilometres, four camels are neck and neck and Najim’s animal is one. Under his scarf he recites passages from the Koran.

Motorcycles and pick-ups spin on the track and their drivers scream but the jockeys pay them no heed.

Their only aim is to coax their camels to go ever faster in the final sprint to the finish.

“It was a terrible final sprint,” Najim says.

“Even more terrible for me because I’m fourth.”

The four frontrunners are soon brought in front of the platform where Nigerien President Mohamed Bazoum is installed.

Little Moussa is grinning broadly after his victory on a camel named Mahokat (“the madman”).

Mahokat’s coach, Mohamed Ali, is happy but not surprised.

Before the race, he had predicted: “This camel is a winning camel. This very day, inshallah.”

Such prized camels may live in the depths of the desert but they are known across the region: regularly winning races. Their owners are rich, but say they are not looking for money.

“There are prizes of course, but they are not what interest us. It is to win,” Hassan Mohamed, owner of a large stable, says with a smile.

“We are looking for pleasure and glory alone.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT