Tuntut jati diri Orang Asli,

Tuntut budaya Orang Asli,

Tuntut maruah Orang Asli,

Tuntut ilmu Orang Asli,

Tuntut itu, tuntut ini,

Tuntut apa?

—Tuntut, the first short story collection by Semai tribal writer Akiya, and the first literary work by Malaysia's indigenous people.

Word of mouth

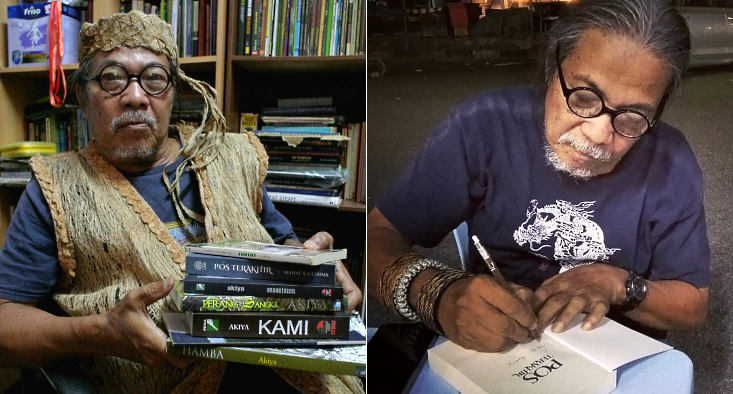

"Why are outsiders so passionate about writing about us the indigenous people?" Perak-born Semai novelist Akiya asked.

Akiya started writing in such a skeptical attitude, and that was more than two decades ago!

The Orang Asli of Malaysia do not possess their own language. All they have are legends and historical accounts passed down by the word of mouth through the generations.

As such, all his works numbering seven to this day have been penned in the Malay language.

Published in 2000, Akiya's first short story collection Tuntut was touted as the country's first literary work by an Orang Asli writer.

"That's what they told me. Probably…" he said humbly.

Back then Akiya did not have much ambition. All he wanted was to see his works displayed on a book shelf.

Bad stereotypes

In mid-June this year, Pusat Sejarah Rakyat organized a webinar in which anthropologist Wan Zawawi had a discussion with Akiya over his novels "Perang Sangkil" and "Hamba".

Wan Zawawi had very high regards for Akiya's works and commented that they should be included in the national education curriculum to give our students a better insight into the country's history and culture from the perspectives of the indigenous people.

Akiya said people started to buy books from him after that webinar, claiming that some publisher was willing to translate his works into English.

Akiya was delighted at such an idea, as this would help spread the thinking of the indigenous people.

"To me, a book has legs, and it can move around, traveling north to south, east to west, anywhere…"

He put it very frankly that in the past, works on Orang Asli by outsiders were either disparaging or partially distorted.

He cited the example of Putera Gunung Tahan by the late Malay writer Ishak Haji Muhammad (Pak Sako) which depicted the indigenous people as dirty, barbaric, foolish and timid.

An indigenous bridegroom would have to chase the bride around the anthill for seven rounds, failing which the wedding would be called off.

"What if the girl is athletic? How are the guys going to get a bride?"

Such filthy and uncivilized stereotype is still firmly cemented in the minds of many to this day.

Akiya discovered that most of the books by outsiders were leaning towards preaching and often ended in intermarriages.

"Perhaps they thought it would be easier to control Orang Asli after they were converted to Muslims, but everyone has the freedom to think, and not every indigenous people would choose Islam. Some have become Christians or are animists.

Having read so much about Orang Asli not from their own perspectives, Akiya made up his mind to start writing.

"Let an Orang Asli write the stories of Orang Asli!"

Hunted and enslaved

Akiya's books invariably touch on history. The backdrop of his latest work "Ludaad" is the Emergency period from 1948 through 1960, when 30,000 indigenous residents supported the communists to fight the colonial government.

"Perang Sangkil" published in 2007 is a blend of historical epic and Akiya's imagination about the hunting and enslavement of the indigenous people by the Malays in 1870s.

The sequel "Hamba" published in 2013, is about the enslavement of male Orang Asli and forced subordination of young Orang Asli women as wives and concubines after the Sangkil war.

That was a very important part of the history of Orang Asli.

Another Semai tribesman Yok Serani Siwah can still remember the details passed down to him from the ancestors. Back then the Orang Asli were constantly hunted down, pursued, and scattered in many small enclaves. They escaped to the upstream of Slim River, Bidor River, and places like Tapah and Chenderiang.

Documentary film "The Tree Remembers" by Malaysian director in Taiwan Lau Kek Huat, followed Akiya and Yok Serani Siwah into Orang Asli settlements to visit places where Orang Asli used to be massacred and hunted.

Akiya insisted that this part of the history ought to be learned by more people.

"I always remind myself to write according to the truth. Imagine looking at our own reflections in the mirror, is the image distorted or too impeccable? If it is, we must rectify it. This is utterly important!"

Start with five words

Jeritlah sekuat-kuatnya,

Supaya orang tahu,

Kamu di situ,

Kamu sakit.

Akiya chanted the words he wrote. He is such an expert in vocal expression because before he became a writer, he used to be a radio announcer for over three decades.

"I learned story-telling from my mother," he said.

When he was young, there was no TV or radio at home. Every night, the siblings would gather around their mother listening to the legends read in the Semai dialect. The story would continue the next day in case the kids fell asleep in the middle of the story-telling.

Influenced by his mother, Akiya became a radio announcer with RTM in 1974. He also wrote radio scripts, edited the programs and read the news.

In order to write the stories of Orang Asli, he went around collecting information, spent long hours in a library, and saved up to buy academic books about the indigenous people in this country.

To Akiya, there is not much difference between radio hosting and writing.

"Before you turned on the mic, everything you say has to be first conceived in your brain. The same goes for writing, the nib of the pen can think."

As such, the information he collected over the years for his radio programs has now become the materials for his literary works.

There was this time anthropologist Wan Zawawi asked him why the indigenous people didn't write, and Akiya quietly took out his manuscripts which eventually went published in 2000 as "Tuntut".

"Unfortunately few among the Orang Asli actually read."

Akiya recalled that no Orang Asli readers showed up when he was hosting book club events on a number of occasions at the National Academy of Art, Culture and Heritage (Aswara).

He often asks, why don't Orang Asli write? Is it that difficult to be a writer? Or is it just a day dream?

Of course it is not easy to write a 500-page book, but then we can always start with writing five words first.

Akiya subconsciously murmured a few lines:

Saya mahu buku saya jadi (I want my book a reality)

Buku saya akan dibaca (my book will get read)

Siapa pembaca buku saya? (who will read my book?)

Semua orang boleh baca buku saya (everyone can read my book)

Buku saya laku di kedai (My book sells like hot cake in bookstores)

"Beginning with five lines and five words, slowly a 500-page book will come into being!"

Akiya hopes the indigenous people can write their own history.

"It doesn't have to be thick. Five of six pages is good enough. We'll first put the stories together and then get someone to edit."

Perhaps not everyone has the ability to write in his or her lifetime, but their kids, grandchildren, they can continue writing!

To Akiya, the Malays were more progressive because they wrote, and from there established their nationalistic spirit to confront the colonial government.

"Why can't we do the same? To me, writing is also a form of struggle!"

Akiya admits that his children and grandchildren are not actually interested in their own tribe's stories.

For all these years, Akiya has been diligently compiling tribal stories passed down to him by his mother and other seniors, but sadly some were lost to computer breakdown.

Anyway, he hopes his children can continue with his works which will be a very important cultural legacy he leaves behind.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT