A year after the emergence of COVID-19, the global community continues to contend with the effects of the pandemic, with Malaysia adopting multiple Movement Control Order (MCO) measures to combat the virus.

As a result, healthcare education – notably medical, dental and pharmaceutical education – has been significantly impacted1,2,3 with all forms of face-to-face teaching converted to remote learning.

However, healthcare students disagree that clinical teaching can be conducted effectively online4, consistent with overwhelming support for a return to clinical placements.

The lack of clinical placements has also given rise to arguments and concerns of sub-standard training to clinical practice in the future5.

It has thus been suggested that COVID-19 vaccine prioritization for healthcare students could enable a safe resumption of clinical teaching through placements6, as carried out in Singapore, the United Kingdom, Hong Kong and the Philippines7.

In Malaysia, however, healthcare students are not prioritized in the distribution of vaccines. Names and details of dental students were submitted to MOHE and MOSTI, but most of them, especially from private universities, were not given their allocations.

Healthcare students are categorized under Phase 3 of the vaccination program, indicating they will be among the last to receive the vaccine8.

Therefore, the Malaysian Healthcare Students Alliance (MHSA) urges the government to prioritize the vaccination of healthcare students for the following reasons.

1. The quality of healthcare education is severely affected due to lost clinical placements and hours

The transition of healthcare education to an online platform has significantly impacted its quality.

The loss of face-to-face teaching and clinical placements has severely disrupted the acquisition of clinical skills and patient communication skills.

Medical education can be broadly split into pre-clinical and clinical medicine, where pre-clinical years of medical school are designed to deliver basic clinical knowledge via laboratory sessions and simulations9, while clinical years enable students to start integrating their knowledge into patient care10.

Both stages of medical training have been substantially altered by the social distancing measures that are in place, with numerous modifications having been adopted by universities to optimize clinical learning11.

However, clinical experience is often irreplaceable, leading final year medical students to feel unprepared in commencing clinical work12,13.

Similarly, public confidence in medical graduates who have received largely online learning could be undermined.

Additionally, dental education has been similarly impacted.

Dentistry is a competency-based field which requires students to undertake ample clinical hours. Key dentistry skills are almost always only developed through close contact with patients via aerosol-generating procedures which comprise a large segment of dental teaching.

Hence, with this enhanced risk, chairside dental teaching has been strictly forbidden during the MCO periods, interrupting the delivery of quality dental education.

This loss of clinical hours further impeded the acquisition of crucial dental practical skills, including but not limited to, communication skills, history-taking and fine motor skills14.

Furthermore, the replacement of laboratory practical with video-viewing and report-writing has resulted in loss of hands-on experiences in pharmaceutical students15, thereafter having inadequate training in the operation of pharmaceutical instruments.

Additionally, discontinuation and replacement of clinical placements with online case studies further impede the development of real-life patient counseling skills16 which are extremely crucial in the daily role of safe and effective dispensation of medication.

2. Risk reduction and provision of protection for healthcare students due to the nature of procedures and clinical involvement

Despite the transition to online learning, the minimum requirements for clinical attachment remain compulsory. This has particularly affected dental students.

All dental students, amidst the pandemic, are expected to complete their clinical requirements which are Minimum Clinical Experience (MCE) and Expected Clinical Experience (ECE), as revised four times by the Dental Dean's Council and the Malaysian Dental Council due to the pandemic.

To achieve these, clinical dental students are required to perform high risk aerosol-generating procedures similar to those performed by dentists in clinical settings.

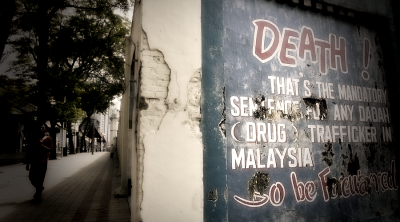

Albeit strict infection measures, these procedures carry an extremely high risk of transmitting aerosol transmitted viruses, such as COVID-19.

As a result, these students are in a highly vulnerable position of contracting the virus.

Compounding this is the risk of COVID-19 carriership among these students, resulting in their families, tutors and peers being infected17.

These risks are similar in medical and pharmaceutical students (especially the third year and final year pharmaceutical students) who are required to attend clinical placements.

3. Delayed graduation of healthcare students resulting in disruptions to the supply of healthcare professionals in the fight against COVID-19

As the pandemic stretches into a third wave, it is clear that a continuous supply of well-trained healthcare professionals is essential to permit the continued operation of our hospitals.

This continuous supply is under threat from the disruptions in healthcare training, with new intakes being delayed and existing students creating a backlog.

Hospitals have understandably limited student participation to reduce risk of transmission and prioritize patient safety.

However, while this preserves the safety of healthcare students, it runs the risk of actively causing a continuous strain on human resources, not only for schools but also for hospitals in need of more trained staff.

For example, once vaccinated, medical students can provide much needed relief for the shortfall in human resources after specialized training18. Furthermore, clinical dental students face the risk of delayed graduation as a result of clinical experience requirements. This leaves students helpless as to how they should graduate on time and be competent in carrying out their clinical duties in the workplace.

We believe that early vaccination would significantly decrease the risk of infection and transmission while enabling their return to clinical settings.

This will not only allow students to graduate on time with required competency levels, but also to contribute to the overwhelmed Malaysian healthcare system.

Moving forward, we would like to call upon the following parties to act.

– Jawatankuasa Khas Jaminan Akses Vaksin COVID-19 (JKJAV) jointly administered by MOH and MOSTI. to amend policies to allow medical/dental/pharmaceutical students who are set to undertake clinical attachments to receive priority access to COVID-19 vaccines (irrespective of vaccine type), and work with university authorities to ensure that all students with anticipated patient contact are automatically registered to receive the COVID-19 vaccine (i.e., opt-out rather than opt-in).

– Public and private university authorities, to work with relevant authorities in ensuring that all students at enhanced risk of contracting COVID-19 due to patient contact are automatically registered for COVID-19 vaccines. We hope that the universities can work with hospital authorities to allow fully vaccinated students to resume clinical attachments so as to address aforementioned issues.

– Healthcare student societies or organizations, to address vaccine hesitancy and increase vaccine uptake circles, thus ensuring high vaccine uptake in healthcare student circles, and to assist with ongoing advocacy efforts for healthcare students to receive priority access to vaccines.

In conclusion, MHSA urges the government of Malaysia and other relevant stakeholders to provide priority vaccination for healthcare students.

While efforts to achieve high vaccination rates within Malaysians must be applauded, the aforementioned issues will only snowball into larger, systemic issues that will persist beyond the pandemic if left unaddressed.

MHSA genuinely believes that fully vaccinated healthcare students and graduates would be a potent addition to aid the ongoing efforts against COVID-19.

References:

1 Rashid AA, Rashid MR, Yaman MN, Mohamad I. Teaching Medicine Online During the COVID19 Pandemic: A Malaysian Perspective. Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 06];19:77-80.

2 Efendie B, Abdullah I, Yusuf E. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Pharmacy Education in Malaysia and Indonesia. Sr Care Pharm [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 06];35(11):484-486.

3 Halim MS, Noorani TY, Karobari MI, Kamaruddin N. COVID-19 and dental education: A Malaysian perspective. J Int Oral Health [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 06];13:201-206.

4 Alsoufi A, Alsuyihili A, Mshergi A, Elhadi A, Atiyah H, Ashini A et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: Medical students' knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 06];15(11):1-20.

5 Jodheea-Jutton A. Reflection on the effect of COVID-19 on medical education as we hit a second wave. MedEdPublish [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 06];10(1).

6 Lim JS, Au Yong TPT, Boon CS, Boon IS. COVID-19 Vaccine Prioritisation for Medical Students: The Forgotten Cohort? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 06];33(8):e359.

7 Ming MF. Vaccinate medical students as early as possible. New Straits Times [Internet]. 2021 May 04 [cited 2021 Jul 06];Letters:[about 2p.].

8 Phases of the National COVID-19 Immunisation Programme [Internet]. Malaysia: The Special Committee On COVID-19 Vaccine Supply (JKJAV); 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 06]; [about 1 screen].

9 Rose S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 06];323(21):2131-2132.

10 Ferrel MN, Ryan JJ. The Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education. Cureus [Internet]. 2020 Mar [cited 2021 Jul 06];12(3):e7492.

11 Nik-Ahmad-Zuky NL, Baharuddin KA, Rahim AFA. Online clinical teaching and learning for medical undergraduates during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) experience. Education in Medicine Journal [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 06];12(2):75-80.

12 Choi B, Jegatheeswaran L, Minocha A, Alhilani A, Nakhoul M, Mutengesa E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: a national survey. BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 06];20(206).

13 Cate O, Schultz K, Frank JR, Hennus MP, Ross S, Schumacher DJ et al. Questioning medical competence: Should the Covid-19 crisis affect the goals of medical education? Medical Teacher [Internet]. 2021 May [cited 2021 Jul 06].

14 Gerzina T, McLean T. Dental Clinical Teaching: Perceptions of Students and Teachers. Journal of Dental Education [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2021 Jul 06];69(12):1377-84.

15 Mohamed MHN, Mak V, Sumalatha G, Nugroho AE, Hertiani T, Zulkefeli M et al. Pharmacy education during and beyond COVID-19 in six Asia-Pacific countries: Changes, challenges, and experiences. Pharmacy Education [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 06];20(2):183-195.

16 Sha'aban A, Ibrahim B, Albitar O, Mohiuddin SG, Omar CG, Harun SN. Transition to online teaching and learning for clerkship activities during COVID-19 in Malaysia. Pharmacy Education [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 06];20(2):7-8.

17 Riva MA, Paladino ME, Belingheri M. Healthcare students: should they be prioritized for COVID19 vaccination? European Journal of Internal Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Jul [cited 2021 Jul 06];89:124-25.

18 Menon S. MMA: Let housemen, medical students join Covid-19 fight. The Star [Internet]. 2021 Jun 04 [cited 2021 Jul 06];News:[about 2p.]

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT