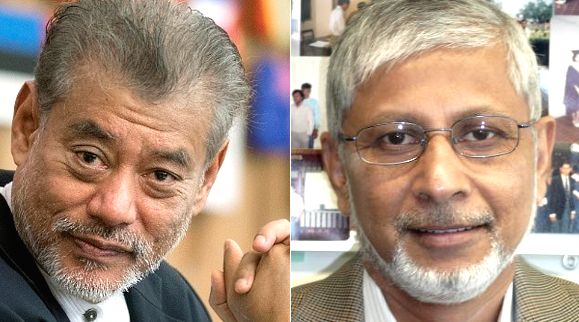

By Anis Chowdhury / Jomo Kwame Sundaram

With uneven progress in containing contagion, worsened by the breakdown in multilateral cooperation due to mounting US-China tensions, recovery from the COVID-19 recessions of the first half of 2020 is now expected to be more gradual than previously forecast.

Pandemic response measures

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, many governments, especially of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies, have introduced massive fiscal and monetary packages for contagion containment, relief and recovery.

Such efforts represent a U-turn after long eschewing counter-cyclical fiscal policy, mostly for ideological reasons, such as dogmatic commitment to 'budgetary balance' and 'fiscal consolidation', besides giving central banks more economic policy discretion since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (GFC).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated new government measures through mid-June 2020 at almost US$11 trillion. The Fund projected new borrowing by all governments to rise from 3.7% of global output in 2019 to 9.9% in 2020.

Projecting gradual recovery from the second half of 2020, the Fund expects average fiscal deficits to rise by 14% as global public debt reaches an all-time high, exceeding 101% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020-2021.

After much wrangling, EU leaders compromised on a new US$2.1 trillion (€1.8 trillion) package on 21 July. The European Commission has also activated the general escape clause in EU fiscal rules, allowing deficits to exceed 3% of GDP.

Complementary monetary initiatives include relaxing recommended Basel 3 capital buffers, lowering mandatory reserve ratios and easing terms for additional temporary credit facilities for banks and businesses.

Thus, central banks have committed an estimated US$17 trillion to extend 'unconventional' measures to buy corporate bonds, besides government bonds and government-sponsored mortgage-backed securities introduced during the GFC.

Windmills of financial minds

Macroeconomic economic policy makers must resist quixotic impulses to fight against financial 'windmills of the mind', instead fulfilling their responsibility to pursue consistently counter-cyclical macroeconomic policies.

Financial market analysts exaggerate real concerns, even using discredited research. Citing old research, even doubted by The Economist, a Forbes columnist insisted that "the surge in government debt" would cause "economic growth to decline", claiming that government debt beyond 85% of GDP would slow growth.

Global public debt came to 83% of world output in 2019, up from 60% in 2008, before the GFC. This sharp rise happened despite austerity measures since 2010 when many G20 and OECD countries adopted fiscal consolidation.

That turn to austerity followed advice from the IMF, OECD and European Central Bank, who invoked influential, but misleading academic research. But fiscal consolidation "after the Great Recession was a catastrophic mistake", concluded a Forbes columnist. It failed to deliver robust recovery, let alone sustained growth.

Subsequent IMF research found fiscal consolidation raised short-term unemployment, with even harder impacts in the long-term, hurting wage-earners much more than profit- and rent-earners. IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard and his colleagues found Fund advice for early fiscal retrenchment inappropriate.

Windmills can block recovery

Reversing emergency expansionary measures too soon risks aborting recovery and may even trigger new recessions. Even an assets fund manager has acknowledged, "Like a course of antibiotics, an economic relief package is most efficacious when administered to completion".

When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt tried to balance the budget in 1937 after securing re-election, the ensuing downturn ended the recovery, only revived after deficit spending resumed in 1939. Also, countries that abandoned fiscal expansion for consolidation from 2009 had worse recovery records than others.

Deficits and debt have, in fact, not been reliable indicators of long-term growth prospects. Obsessed with debt and deficits, while ignoring spending composition and efficiency, 'deficit hawks' tend to downplay the potential growth impacts of expansionary fiscal policy.

Nevertheless, the Fund continued to warn in January 2019 that high and rising public debt constituted "a potential fault line". Pre-pandemic economic stagnation, tax cuts and poor commodity prices induced larger fiscal deficits, requiring more government debt, now compounded by COVID-19 containment, relief and recovery efforts.

Clearly, government macroeconomic policies should not be guided by financial market whims. Leaving policy making to such influential market signals can push an economy in recession into a lasting depression. The recent IMF leadership transition appears to have led to greater pragmatism just in time.

Investing for the future

The Fund's April 2020 Fiscal Monitor urged governments to take advantage of historically low borrowing costs to invest for the future—in health systems, infrastructure, low-carbon technologies, education and research—while boosting productivity growth. After all, a year ago, advanced economies were spending only 1.77% of their combined GDP on debt interest—the lowest since 1975.

Unusually, it also advised governments to enhance automatic stabilizers, including a tax and benefit system to stabilize incomes and consumption, involving progressive taxation and social security payments or unemployment assistance.

Undoubtedly, politicians are often tempted, by lower debt costs, to borrow to spend more on "populist" programs while cutting taxes. Such irresponsible fiscal policies need to be corrected.

Clearly, governments need to look at how money, borrowed or otherwise, is spent. If, for example, borrowed money goes into investments enhancing productivity, public assets can contribute not only to growth, but also to revenue.

COVID-19 recessions are quite different from recent ones following financial crises. Yet, all recessions threaten to become depressions if not quickly and appropriately addressed.

We are in for a long hard struggle, on both public health and economic fronts. Policies must not only be appropriate for the problems at hand, but should also create conditions for a better future, rather than simply trying to return to the status quo ante COVID.

As visionary leaders did during and after the Second World War, we need appropriate plans, not only to revive economies and livelihoods, but also to build a more dynamic, sustainable and equitable economy.

This article was originally published on Inter Press Service IPS.

!function(d,s,id){var js,fjs=d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0],p=/^http:/.test(d.location)?’http’:’https’;if(!d.getElementById(id)){js=d.createElement(s);js.id=id;js.src=p+’://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js’;fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js,fjs);}}(document, ‘script’, ‘twitter-wjs’);

(Jomo Kwame Sundaram, a prominent Malaysian economist, is Senior Adviser at Khazanah Research Institute, Visiting Fellow at the Initiative for Policy Dialogue, Columbia University, and Adjunct Professor at the International Islamic University; Anis Chowdhury is Adjunct Professor, Western Sydney University and University of New South Wales, Australia.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT